We’ve partnered with Falko to bring you more free analysis and charts. Roughly once a month, we’ll include a second analysis for the week on one of our favorite and least understood markets: regional aviation. Of course, our regularly scheduled programming will arrive on Thursday as usual. If you would like to skip to the pdf download of this analysis, you will find it here: https://visualapproach.io/mp-files/the-art-of-misunderstanding-regional-jet-residual-values.pdf/

Small jets are certainly not new in commercial aviation, but the term “regional jet” is still in its 30s. The DC-9, F28, BAe-111, and 146 were all commonplace prior to the regional jet name.

With the arrival of the CRJ100 in 1992 came the title for a new class of aircraft - the regional jet. Joined by Embraer’s ERJ-145 in 1996, the two jets were a new, economical way of moving 50 passengers. The key difference between this new class of small jets and the largely unsuccessful classes before it was the airlines which operated these 50-seat jets.

Rather than being the smallest aircraft on the expensive mainline pilot payrolls, the new 50-seat jets were distributed to the regional airlines, delivering economics that would make this new segment wildly successful – almost too successful.

This analysis considers how the early success of the 50-seat jet created a unique situation in aircraft values across all of commercial aviation. It is a story that is well known across the industry: 50-seat jets prove regional jets do not hold their value.

It is a story that is also completely wrong.

We will examine why the 50-seat jet was so challenged in retaining value, and what it means for the larger jets flown by the same regional carriers. Finally, we will compare the various classes of regional jets across all commercial aircraft, including the benchmark of the world’s largest narrowbody fleets.

What happened with the 50-seat jet?

The 50-seat jet remains in service with airlines around the world; however, the incredible success it once saw was largely limited to North America. Driven by pilot contracts that limited the number and size of aircraft that could fly at the large U.S. airlines, this new 50-seat jet was the perfect candidate to be flown by the smaller and cheaper regional airlines.

Largely limited to smaller turboprop fleets, the regional airlines were keen to find new growth through the new regional jet technology. The larger mainline airline partners were equally interested in the type. Not only did the new small jets offer superior economics to mainline aircraft, but the revenue benefits were also equally as powerful. No longer were passengers in small and medium-sized cities limited to a few connecting options through busy hubs on small turboprops. The regional jet opened up new flights, allowed the reduction of two-stop connections, and ultimately offered passengers more non-stop options.

The value for airlines to transition to the 50-seat jet was three-fold:

It brought a yield benefit from passengers looking for increased flights and connection options

It was an effective competitive weapon against airlines with strong regional hubs which could now be overflown, and

The 50-seat jet was the most effective defense against the incursion of other 50-seat jets during downturns or exceptionally strong markets.

If ever there was a fear-of-missing-out (FOMO) event in commercial aviation, this was it. Not only did airlines need 50-seat jets to steal market share from other network airlines, but they needed the type to defend their own. The result was a parabolic growth rate – near vertical by 2000 - in the number of 50-seat jets delivered, with the vast majority delivered to the United States.

Of course, a pace of growth this rapid cannot be sustained indefinitely, and the 50-seat jet was no exception. By 2001, the market for 50-seat aircraft was largely saturated as both an offensive and defensive tool against itself. The peak of the 50-seat jet coincided with the arrival of the downturn in 2001 following the September 11 attacks.

The once-profitable network airlines fighting for ample revenue and a yield edge suddenly found themselves losing money. Making matters worse, the yield premium once brought by the 50-seat jet vanished as nearly all network airlines deployed them in some capacity. No fewer than eight U.S. network airlines deployed 50-seat jets by the early 2000s. The competitive edge driven by the new regional jet technology evaporated as all airlines employed it.

However large the 50-seat fleet had become by the early 2000s, values remained steady. Rather than a change in the economy, it would be a change in pilot contracts that would ultimately doom 50-seat values.

By the early 2000s, mainline pilot contracts began allowing exceptions within their scope clauses for larger regional jets to operate at the regionals of the parent airline. Coinciding with the arrival of the 70-seat CRJ700 in 2002 and later the E170 in 2004, regional fleets, once capped at 50 seats could now grow beyond into larger aircraft. Without access to

70-seat market before, the 50-seat jet remained the most economical alternative and sold into a market better suited for the larger regional jet. Suddenly, the better alternative arrived with the 70-seat jet, putting the smaller 50-seat jets into an oversupplied scenario.

This trend toward larger 70-seat jets continued. As contracts were negotiated, more 70-seat jets were allowed, eventually allowing 76 seats. This served to further reduce the need for the substantial 50-seat fleet already in service. During the decade, each of the large U.S. network airlines would find itself transiting through the Chapter 11 bankruptcy process.

However, it would not be bankruptcy that would hurt 50-seat values as much as the mergers that would eventually follow. The eight network airlines deploying 50-seat jets would ultimately merge into three large network airlines: American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, and United Airlines.

Suddenly, routes that provided competitive service on 50-seat aircraft to multiple hubs could now be consolidated into larger aircraft. Network models suggest the market which held nearly 1,500 50-seat jets now needed fewer than half that number. Residual values plummeted.

Ten-year values of 50-seat jets would drop nearly 80% during the following decade. Even as production of 50-seat jets shifted to the new large 70- and 76-seat jets, 50-seat values continued to drop through 2020. The airplane was simply not required in the numbers that were supplied.

For an industry shifting its attention to the mammoth narrowbody market and away from the nuances of the regional jet, the warning was as simple as it was inaccurate: regional jets do not retain value.

Missing the value of the large regional jet

The years that followed brought more scope changes to U.S. airlines, and a further shift in the type of regional aircraft required. Having moved from 50 to 70 seats, scope clause exemptions for regional jets ultimately settled at 76 seats – a dual-class configuration for the CRJ900 and E175.

Just as the shift in scope clauses to allow for 70-seat jets affected the 50-seat market, so too would the 70-seat market by the shift to larger 76-seat jets. However, what made this shift to the 70-seat CRJ700 and E170 aircraft different from the rush into the 50-seat market was a limitation on the number allowed and reduced production. Even as deliveries shifted to the 76-seat variant, scope clauses still allowed explicit room for 70-seat aircraft, ensuring a need for these aircraft to continue operating.

As a result, while 50-seat jet values were plummeting, 70- and 76-seat values remained stable.

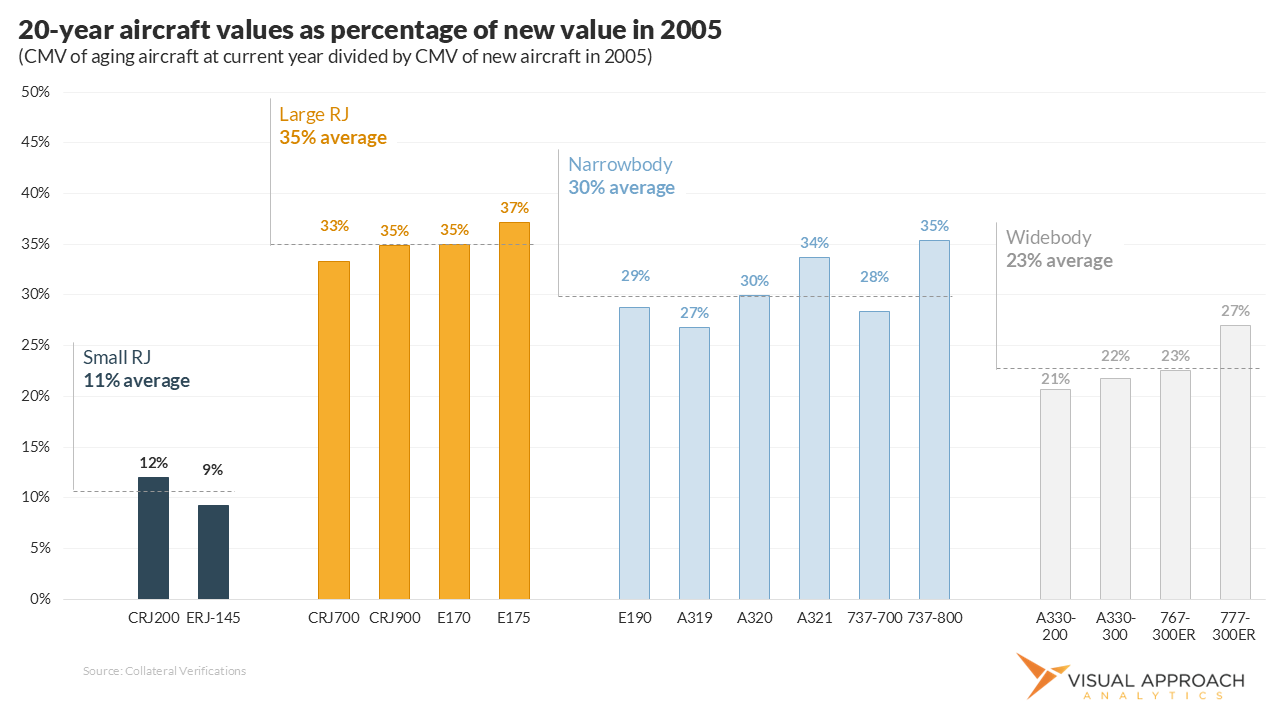

Comparing the current market value curve for a 2005-built 50-seat jet with a 70- or 76-seat jet built in the same year showed a stark contrast. By 2015 and at 10 years old, the large RJs retained 51% of their new value, compared to only 18% value retention by the 50-seat jets.

Just as the 50-seat fleet produced significantly more aircraft, so too did the drop in values produce significantly more attention. Investors who assumed all regional jets were valued as a single sector would have missed that the residual value retention of large RJs were three times better than the 50-seat fleet. In fact, by 2015, the large RJs of the CRJ700, CRJ900, E170, and E175 families were maintaining value better than the average narrowbody, the industry benchmark for stable values.

The reason for this value stability is simple when large RJs are looked at in isolation. The 70- and 76-seat aircraft were still largely North American-based but were not subject to a rush into the type as a means by network airlines to defend against competitors doing the same. Similarly, production levels remained stable for the large RJs, a contrast to the large spike in 50-seat aircraft ordered by airlines.

Just as critically, the pilot scope clauses that initially allowed 50, then 70, then 76 seats stopped expanding. This created two very different markets into which the 50-seat jet was ordered than was present for the larger RJ. While the 50-seat jet grew with unlimited restriction into a market of unknown

size, that size was better defined, and with finite limits to the number of large RJs that could be purchased.

Between 2000 and 2010, pilot scope clauses changed over 15 times across the various airlines. In the past 10 years, there have been no material changes in scope clauses, nor do we expect there to be in the foreseeable future, cementing the large regional market around the 70- and 76-seat jet.

The result was a remarkably rational entry into the market for the large RJs when compared to the race to find 50-seat jets. Value stability has inevitably followed this market stability.

Putting regional jet values back into context

The large regional jets of the CRJ700, CRJ900, E170, and E175 are typically contrasted with the 50-seat market, and understandably so. Similarly named and grouped as “regional jets”, both sectors represented the same two manufacturers, spanning a single aircraft family in the case of the CRJ. But, for operators or investors who considered there to be one ‘regional jet’ market, significant value was missed.

Even though the large RJ has maintained such a strong lead in value retention over smaller 50-seat jets, the more meaningful comparison is to the narrowbody. Appropriately defined as the standard in value retention, the narrowbody dominates the commercial aviation market. Narrowbody aircraft are produced at 10 to 15 times the rate of regional jets, creating a market that swamps that of the large regional jet.

Yet, despite the order of magnitude difference between the two markets, the large regional jet has better maintained values over the past 20 years than the ubiquitous narrowbody. This benchmark of stability set by the narrowbody has been exceeded by the large regional jet – a realization lost when combining all jets under 76-seats into one ‘regional jet’ bucket.

In this renewed context of the narrowbody, any comparison of value between the large regional jet and the 50-seat jet becomes even more challenging. This is not to say the large regional jet should be considered a narrowbody. The two markets are subject to distinct differences.

The large regional jet market will never be as large as the narrowbody, nor as globally distributed. Further, this aircraft is primarily a tool of the network airline, providing the most economical solution for connecting vast networks. The narrowbody, on the other hand, also finds distinct value as a low-cost platform, free from the restrictions of pilot scope clauses. Indeed, this is the key market differentiator between large regional jets of the E170 and E175 and the small narrowbodies of the E190, E195, and A220. Even sharing family nomenclature, the E175 and E190 are destined for different markets altogether.

Yet, just as wide differences exist between the large regional jet and narrowbody market, so too do they exist between the large regional jet and 50-seat jet market. It is only with the acknowledgement that the regional jet market as a whole is sharply separated between large and 50-seat jets that the value of the best-performing sector can be identified. Subject to none of the factors which turned the 50-seat jet into the worst-performing market, one only needs to look 20 seats larger to find the best-performing.

In this way, the story told by the 50-seat jet was its story, alone. It is the story of the large regional jet that has since been written separately. That story is one of value retention, stable market supply and demand, disciplined production and of steady market returns for those investors willing to read it. For investors, the distinction between these markets isn't just academic — it's the difference between writing off an investment and realizing consistent market-leading returns.

Falko is a leading aircraft lessor and asset manager focused on the 70 – 130 seat aircraft segment and is one of the longest standing lessors and managers of aircraft of this size globally. As of 30 June 2025, Falko’s managed fleet totaled 211 aircraft including E170, E175, CRJ700 and CRJ900 aircraft types, representing 36% of Falko’s commercial jet fleet.

If you are interested in learning more about investing in small commercial aircraft, please contact Falko’s Investor Relations team at [email protected]. For further information about Falko, visit their website or follow them on LinkedIn.

For a PDF download of this analysis, you can find it here: https://visualapproach.io/mp-files/the-art-of-misunderstanding-regional-jet-residual-values.pdf/

If you were forwarded this email, score!

As valuable as it is, don't worry; it's entirely free. If you would like to receive analyses like this regularly, subscribe below.

Then...

You can pay it forward by sending it to your colleagues. They gain valuable insights, and you get credit for finding new ideas!

Win-win!