The Dublin meetings are wrapping up under cloudy skies with just enough wind to blow the rain sideways and render your umbrella useless as much more than a sail.

Cold. Windy. Rainy. Miserable.

In other words, perfect Dublin.

The aviation finance community has completed its descent onto Dublin for the week, filling hotels, coffee shops, and restaurants surrounding St. Stephen’s Green. The activity within the warm, dry meeting areas was strong, with many in the community more confident in their optimism about the aircraft industry in 2026.

If you looked closely, you could sense the industry’s power dynamic operating in reverse. Everybody wanted to talk to the airlines, becoming near-celebrities for the week. The lessors and finance community enjoyed the home turf, actively trading and eager to meet.

The airframers were available, happy to answer questions and provide production updates, but without the need for a hard sell. Finally, the engine OEMs were answering the tough questions, honorably fighting what must certainly have been an urge to slip into the background where the questions weren’t so… durable.

This conference dynamic was perfectly opposite to the industry’s power dynamic in 2026.

Who leads the commercial aviation power dynamic in 2026?

(Engines. It’s the engine manufacturers.)

Or What?

We don’t subscribe to the efficient market theory in aviation. There is always an information edge somewhere, and the week in Dublin proves most agree.

But we do subscribe to the “Or what?” market theory. This theory (invented merely seconds ago) perfectly defines the power dynamic at play in aviation today. You can get in the long line for new aircraft deliveries or…what? You can put up with low new technology engine durability and double-digit spare parts escalation or… what?

Each major sector in aviation rests on the “or what?” spectrum. It’s a simple hierarchy in 2026: engine OEMs → airframers → lessors → airlines.

Tier 4 - The airlines

The airlines may be the celebrities at the conferences, but they find themselves at the bottom of the hierarchy. In the commercial aircraft world, it’s a seller’s market, and airlines are the buyers.

Upfront deposits are required for airplanes that show up years later for prices that escalate, reliant on continued support and parts sold for rates that only escalate faster. New aircraft backlogs are almost better measured in decades than in years, requiring airlines to commit to future deliveries that are set to arrive during the next business cycle (assuming they survive the current one). The only reprieve available for fleet managers in recent years was that the airlines’ desperation for capacity was exceeded only by investors’ desperation to deploy capital. See: Sale and Lease-Back.

Luckily, the constrained capacity has allowed profitability to return, but the days of continued high profitability and high growth are in question. To maintain profitability, the airlines need lift, and the rest of the industry knows it.

Tier 3 - Lessors and investors

The next rung up finds the lessors and aircraft investors, happy to ride the wave of asset appreciation and feed the airlines what constrained capacity they have. Still subject to high escalation rates and expensive maintenance costs, the most common complaint from lessors today is not the demand for leased airplanes; it’s that they can’t find the airplanes to lease.

The number of speculative orders held by the lessors is incredibly low, driven by the airframers’ realization that in an aircraft shortage, you don’t need the middleman to move product. (That will inevitably change, but only with the downturn nobody wants; the proverbial Catch-22).

Tier 2 - Airframers

Meanwhile, Boeing and Airbus are struggling to meet production targets, still with a gaping hole in the market from production shortfalls during COVID and other production stoppages. Yet, one rung further up the hierarchy, the two airframers find themselves near the top of the “Or what” hierarchy (but not the top).

“I’m sorry your delivery will be late. You could wait for it to deliver several months late, or… what? Perhaps you could get in line at our competitor and wait 10 years. Also, here’s our new escalation formula.”

It’s not underhanded. It just is. If you need a new big airplane, you’re stuck. A or B? Get in line. Or what?

But, as good as it is to be an airframer today, even they must defer to the top of the hierarchy in 2026: the kings of the hill, the top dogs, the big cheeses…

The engine manufacturers.

Tier 1 - Engine OEMs

This didn’t used to be the case. Boeing and Airbus used to be able to create sufficient competition between the engine makers that they would compete to be on aircraft programs. Today, it’s a bit different.

The old business model was simple: lose money on each engine delivered, then make it up in the services and aftermarket. It’s the business model still in place today, old as it may be.

But the airframers, once keen to make the engine OEMs dance for the opportunity to be mounted on an aircraft program, are now dancing themselves, nervously waiting for engines on which the late airplanes are waiting.

And when those engines do deliver, the durability has only gotten worse (or better, depending on which side of the buy/sell equation you sit). Parts escalation has exceeded double digits annually, broken only by GE offering a single-digit escalation twice a year (we’ll let you do the math to find the marketing genius in that one).

Engines are being sent to the shop more often for visits that cost more, driving increased revenue into engine makers' profit centers. Durability mods are coming - if slowly - offering the ability for operators and lessors to buy expensive kits to claw back a portion of the durability originally promised.

If the incentives feel a bit inverted, you’re not alone. But keep in mind that these are forces for which the airframers have been asking for decades. You give me cheap engines, and I let you charge whatever you want to keep them running later.

Even with expensive payouts on the GTF program, if you squint, the $6 billion offered to customers looks less like compensation and more like a loan, repaid not through interest rates but through escalating rates set by the engine manufacturers.

Or what?

It’s not evil. It’s leverage - and the engine OEMs have it. Simple economics.

The power dynamics of the future

Today’s hierarchy is affecting tomorrow’s setup. We wait for the next generation of aircraft to begin development - and we will probably be waiting a while. While endless industry observers send us emails explaining how Airbus and Boeing need to do “something,” we’re left with the sneaky suspicion that it’s not the airframe OEMs who are ultimately making that call. Without a new engine, how “next generation” can it even be?

Then consider the pitch made to the engine OEMs, now content to watch the airframers do the dancing. “We’d like you to spend billions to build a new engine that will lose money up front and replace the engines that are currently driving your record profits.”

Uh huh.

But before you give in to that twinge of sympathy for Boeing and Airbus, think again. The airframers aren’t exactly suffering from the engine challenges - the residual benefits are clear. Constrained supply flows down the system. While delivery numbers may fall below targets, backlogs are at record levels, driving higher pricing and baked-in escalation for years. The stalemate on new technology spend isn’t exactly terrible for them, either.

Lessors don’t want new technology - beyond the whole saving the planet thing. They prefer stability in the space, allowing their assets to drive utility (and returns) for longer.

Leaving the airlines, which aren’t exactly begging for the next big thing either. Fuel is cheap in 2026, but engine shop visits are not. If conversations around Dublin are any indication, airlines would rather the 737NG and A320ceo lines return to production, if for no other reason than to provide visibility on engine costs. Lower fuel burn in exchange for a renewed period of uncertainty with new technologies doesn’t sound like a great tradeoff at $60 a barrel.

And so the dynamic continues: A constrained supply system incentivized to stay constrained. The runway is long, and it’s predictable - this supply setup will be here for years.

It’s the demand setup that could change things while nobody is looking - a setup that holds the sleeper tier in today’s power dynamic: the passenger.

Lucky number 31 - Delta’s Airbus widebody order

Yesterday’s news of Delta purchasing 15 A350-900s and 16 A330-900s triggered an off-cycle micro analysis.

The order totaled 31 aircraft, one more than the recent 787-10 order from Boeing barely a week ago. Is Boeing +1 a coincidence? Hardly.

But there is an easter egg buried in the order. It's not hard to find. Here's a hint: It's a hit song from the 1946 Broadway Musical, Annie Get Your Gun.

The order makes sense for Delta. The incremental 15 A350-900 and 16 A330-900 widebodies from Airbus will add to the existing A350s and A330s in the fleet.

So 31, it is, besting Boeing’s number by one.

I'm reminded of the famous musical hit Broadway in 1946 titled "Annie, Get Your Gun." It's about a woman sharpshooter rising to fame in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. But that's not important.

What I would like to draw your attention to is the hit song from the play. You'll recognize it:

Boeing +1.

Do you believe it is a coincidence?

I definitely don't. But I also don't think Delta is the one that cares so much about the scoreboard.

Which brings us to the next question: How much was that 31st airplane, anyway?

Let me put the question another way: Entirely hypothetically, if that 31st airplane were completely free just to get the scoreboard to a place where - you know - you like it, how much of a discount would it be on the entire deal?

2.7%. Give or take.

Not saying the aircraft WAS free, just that the equivalent can be very easily replicated without actually making the +1 gratis. We'll never know.

So, yeah. In billion-dollar aircraft deals, sometimes it's not just about the math.

Sometimes it's about the song.

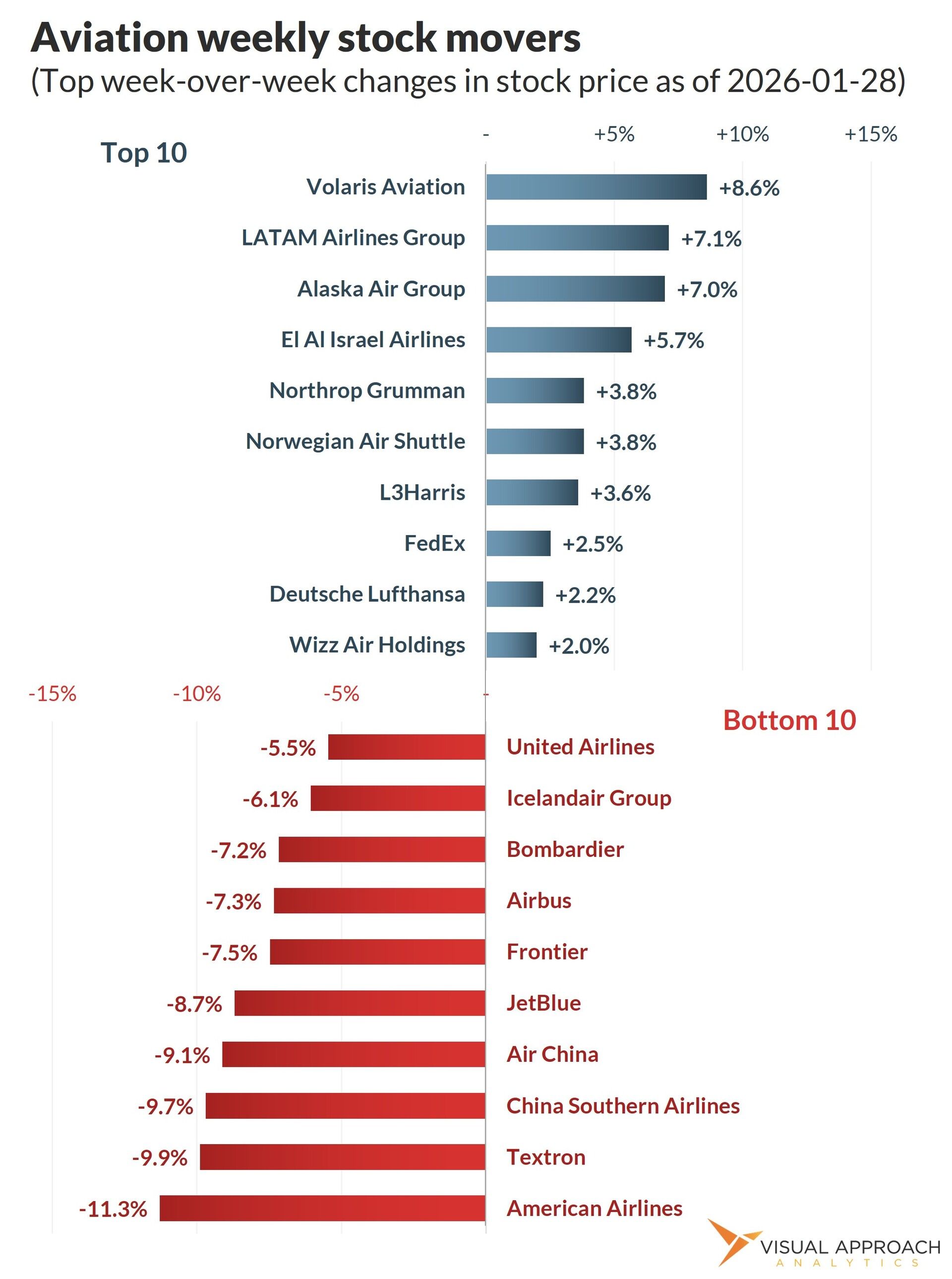

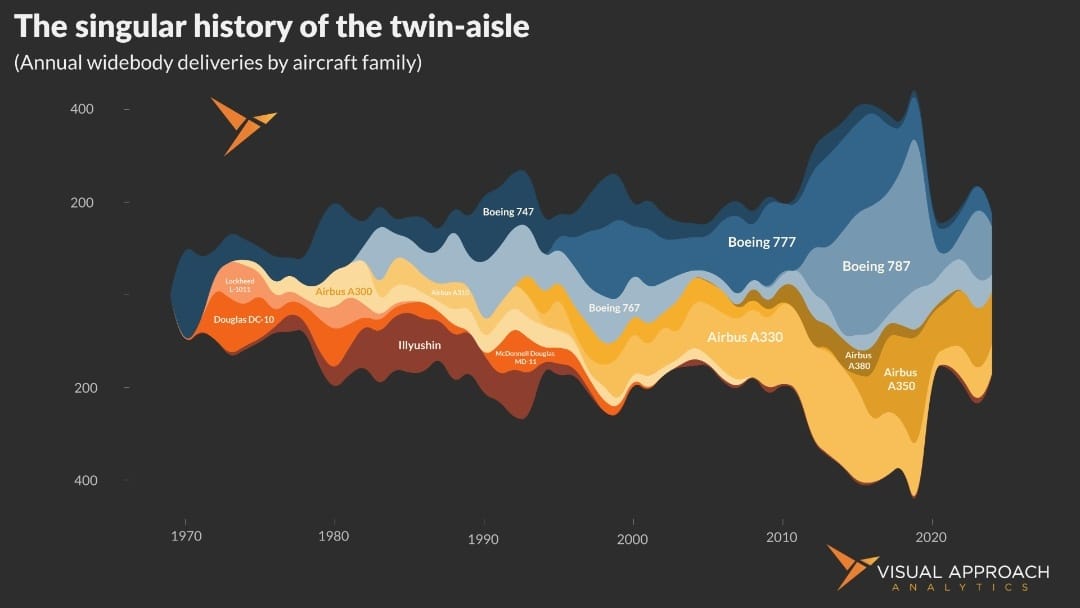

Research published this week

You should do a chart on…

We like to create valuable charts. But it’s not easy to come up with new ideas amid the endless hours spent delivering data-driven edge to our customers. In our quest to provide a valuable weekly newsletter, we can keep guessing what you find most valuable, or you could just tell us.

If you have an idea for data visualization, reply to this email and let us know what analysis you’d find most valuable. We’d love to hear from you and will happily name-drop.

ACCESS OUR DATA AND ANALYSIS

We provide bespoke analysis to investors, lessors, and airlines looking for an edge in the market.

Our approach to analysis is data-driven and contrarian, seeking perspectives to lead the market, question consensus, and find emerging trends.

If a whole new approach to analysis could provide value to your organization, let's chat.

If you were forwarded this email, score!

As valuable as it is, don't worry; it's entirely free. If you would like to receive analyses like this regularly, subscribe below.

Then...

You can pay it forward by sending it to your colleagues. They gain valuable insights, and you get credit for finding new ideas!

Win-win!

Contact us

Have a question? Want to showcase your organization in a sponsored analysis? Reach out.

It’s easy. Just reply to this email.

Or, if you prefer the old way of clicking a link, we can help with the hard part: contact